Whether you’re interested in stills photography or video, you can’t have escaped noticing the ever-higher resolution numbers touted in the specification race. Ever higher numbers of megapixels for still cameras and 6k or 8k video (before many people have even made the transition to full HD), and ever-spiraling costs for equipment, both for production and viewing of image-based media. What does it all mean, where will it end, and how does it really affect your ability to create, or your enjoyment of photographs and movies?

The resolution paradox

When I consider this topic, I’m always mindful of a similar numbers race, which took place in the audio recording industry just after the turn of the century, when digital recording equipment entered a race to leave behind 48khz sampling in favour of 96khz and even 192khz, with 16 bit becoming completely outgunned by 24 bit, etc. Anyone involved rushed out to purchase the latest and greatest gear, boasting ever higher numbers and, of course, commanding ever-higher prices.

However, this trend in the recording industry seemed to fly completely in the face of trends within the listener fraternity, which had, in all but a very few cases, never heard digital audio beyond the 44.1khz resolution of CD. Moreover, at the same time listeners were moving in extremely large numbers away from CD to the much more convenient, but sonically inferior mp3 format as the main vehicle for listening to music. The result of this was and still is, that most consumers almost never hear much of the original resolution that the recording industry has invested considerable resources to achieve.

In many respects, we seem to be facing a similar paradox with respect to digital images, in that as creators become ever more resolution obsessed, viewers are spending less and less time viewing images in a context where this can be appreciated.

Practical reasons for increasing image resolution

More to choose from

There is a sound technical basis for suggesting that, despite the eventual playback resolution, capturing the maximum amount of information during the recording process will still impact the quality of the final product. Put simply, the more samples a compression algorithm has to choose from, no matter how lossy that compression is, the more nuances of the original are likely to survive the process. Also, higher definition recordings are future-proofed to some degree, because as compression and distribution technology develops, your original recordings can take advantage of it. Both the music industry and Hollywood have benefited a great deal from re-mastering of archival material as digital technology has improved.

Cropping

One of the great conveniences of working in higher resolutions is the ability to crop from frames with higher pixel counts than you actually need for the final product, giving the content maker some latitude during post-production. I must admit, this has certainly saved my life a few times, particularly when shooting video or stills in a less controlled environment, where you simply don’t have time to get too fussy over subject framing. Also software image stabilisation in platforms like Final Cut Pro works on this basis, discarding the giveaway edges of each frame to give a more stable, although somewhat smaller result.

A digital journey

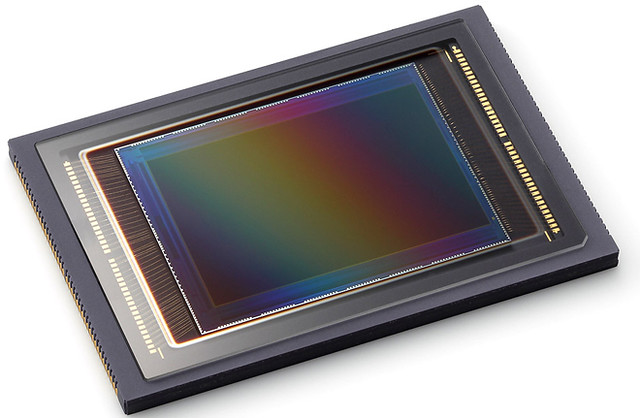

My first DSLR was a 6.3mp Canon 10D, which, apart from anything else, was a really positive step for me, in terms of productivity, from the 35mm film cameras I’d used for the previous 20 years. However, this was undoubtedly at the cost of a drop in image quality from what I’d been used to, as neither the sensor resolution nor bit depth was capable of recording as much information as film emulsions of the time. Upon studying my first DSLR prints as they returned from the lab, I could definitely see the difference between these and their film-originated counterparts and I don’t mind admitting that my heart sank a little. Was the investment I’d just made a mistake?

Reaching resolution Nirvana

I stuck with digital as sensor resolutions climbed through 8 and 10 megapixels, eventually purchasing a Canon 5D, which boasted a 12.8mp sensor and was advertised as officially being higher resolution than 35mm film. My worries were over and my journey on the road to megapixel Nirvana was now well underway. Fast forward 14 years and I now use camera bodies, which boast 26mp sensors, a resolution I could only dream of when taking my first tentative steps into digital some 17 years ago. Indeed, objectively speaking, the digital vs chemical argument has long been over and even relatively modest digital cameras can now produce beautifully detailed images, at low cost, which can be processed with incredible flexibility.

But who’s actually bothered?

There’s no doubt that the imaging capabilities of my cameras have increased significantly since I started using digital, but the reality is that no one ever complained when the resolution of my photographs took a perceivable downturn during my early days in digital. Another reality is that 95% of my commercial photographs are now viewed over the web, highly compressed, and at as little as 72dpi resolution. Alternatively, my print orders almost never exceed A3 in size, which is well below the theoretical print size that can be produced from a 26mp image, at what is still considered good print quality, i.e. 300dpi. OK, I’m not involved in the high end of commercial photography, but for my purposes, going any further in terms of pixel count could certainly be considered a bit of a waste of time.

Video killed the radio star.

I first used a video camera back in 1983, while taking my degree. It was described as an Industrial VHS camera and was a beast and a half. Battery life was circa thirty minutes and the image resolution and quality were truly abysmal! Since then I’ve owned or worked with a number of cameras, including Video8, Digital8, Mini DV, and hard disk models, with my main current camcorder now being a 4K Panasonic CX-350. With each successive generation of camera, resolution, dynamic range, battery life, and audio quality have all improved, sometimes markedly, and I’m often quite gobsmacked by the detail that I’m able to capture with even a relatively low-end professional-grade camera. However, its very clear, from the image quality of many YouTube videos, for example, many of which have eyewateringly large numbers of views, that image quality of any kind isn’t a key criteria for viewer interest.

Whats on TV…or tablet…or phone, tonight?

The shipping numbers for the latest generations of TVs, tablets, phones, and just about every other consumer device continue to rise unabated and I have little doubt that before too long consumer items that we coveted ten years ago, such as 1080p TVs, will soon only be viewable in museums. Consumers always want the latest and best! But ultimately, are they actually that bothered about what this offers?

TBH, when I’m consuming content, even as someone who is more interested in technical aspects of production than most, if I start noticing things like the image resolution, chances are it’s because I’m getting bored with the subject matter on screen! It’s what I describe as the rubber shark syndrome: Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a classic bit of storytelling, that I’m sure will continue to be loved for many decades to come, and the fact that the shark puppet leaves a lot to be desired by modern standards is completely immaterial. If we’re fully immersed in a story, be it a feature film or an advert for washing powder, we simply don’t care about, or perhaps even notice the technical quality of what we’re seeing. The same goes for old photos, classic Film Noir, re-runs of Friends, and so on.

Just over a year ago, I wrote an article that looked at the whole idea of motion smoothing on more modern TVs and the consternation this was causing among high-end content creators because their movies were being well and truly buggered up by this technology, which many consumers didn’t realise was even enabled on their new shiny black monolith TVs. More to the point, most probably hadn’t even noticed or didn’t really care! Another issue causing consternation in the same quarters is the viewing of feature films on mobile devices, as this recent BBC interview with Spike Lee reveals. Like it or not, the trend in consumption is towards convenience, and in the same way that MP3 took over from much higher quality audio formats at the turn of the century, small screen viewing is fast becoming the top dog.

Where will it all end?

There’s no doubt that extinction-level events notwithstanding, imaging and content distribution technologies will continue to improve, and it’s likely that ten years from now, things like cameras capable of sub 20mp stills and 4K video, will only be found as kids toys, complete with big brightly coloured buttons and in-camera emoji overlays. But does it have to be a bandwagon we all jump on, or more to the point, get dragged along by? For now, I’m certainly conscious of the perpetual pressure to upgrade, as that seems to be the way of the industry, and, let’s be honest, I love new kit as much as anyone! However, I’m forced to ask, just sometimes, if I’m being taken for a ride!

Stourbridge-based Mooma Media offers event audio-visual support, event filming, live-streaming, video production, and still photography services to businesses, the public sector, and other non-commercial organisations throughout the Black Country and the wider West Midlands region. To discuss your project, or for a competitive quote click the button below.

Comments are closed